Begin with a tight close reading of the canto’s opening lines to map the revolt that threads through the walls above the gates and sets the moral boundary for the story.

Contributors to the revolt against a rigid order surface in the canto when theyre confronted by mythic imagery, with the allusions to achilles and typhon signaling a tension between heroic memory and chaotic power, a pattern you should know as you trace the canto’s terrain.

Apply a micro-to-macro method: anchor every wall motif, and note when the crowd shouted, when a guard killed, when later the boundary is bound. Connect how the distances between above and below hang together to map the moral topography beyond a single canto. The text seems to indicate a huge wound in the social fabric today, echoing through the walls and gates.

Today, readers can apply this method to other passages, tracing how the canto reframes memory of pride and revolt as a bounded, social drama today rather than solitary punishment. For a practical takeaway, map where the action sits above ground and where the narrative wound to justice is felt, then compare this pattern with other mythic cycles to understand continuity and change in the larger story.

Dante and Virgil among the Giants: Focused Reading of Canto XXXI

Focus your reading on how dantes and virgils handle the encounter again: the steady voice from virgils keeps the pace, directing your gaze toward the giants standing around the bottom rim at the gate to the city. This approach, most simply, shows a strategy built on calm rather than brute force, and it invites you to pursue the path forward there rather than force your way through.

Noted figures there are Nimrod, ephialtes, and Antaeus nearby. The dialogue showcases a curious clash: ephialtes’ outburst, Nimrod’s Babel-like cadence, and virgils’ calm reply. Those lines invite a close reading of how language is used to test rather than conquer.

Looking at form and stance, the giants’ heads loom, their strong frames standing around Dante and Virgils. The scene centers on the neck and shoulder bulk, with a wound-like emphasis in the mythic body. Those people encountered here are not simply obstacles but a test that must be faced before any ascent.

Further, this passage uses imagery to recalibrate fear into purpose. dantes notes the scene with close observation, while virgils offers practical guidance rather than force. The number of participants is small, yet the impact is vast, and the reader feels the weight at every turn.

Conclusion: This portion teaches how to read mythic scale: the Giants are not merely obstacles but a frame for the progression to the eighth segment of the journey; the scene’s tension turns on the contrast between the raw strength of those people encountered and the discipline offered by the guides. The result is a moment that remains most notable for its balance between fear and direction.

| Nimrod | Voice of Babel, blocks the gate with a towering presence | noted for the Babel-like speech; heads loom, neck thick, a symbol of linguistic barrier |

| ephialtes | Outburst figure, testy and loud against the barrier | curious clash; reading the moment shows how such force tests the guides |

| Antaeus | Strong giant near the bottom who anchors the progress toward the pit | his location signals the shift toward the next stage; looking at stance reveals purpose |

| dantes | narrator who observes with care alongside virgils | the two guides shape pace and meaning, turning danger into a turning point |

Identify the giants: who they are and their mythic/biblical sources

The giants are Nimrod, Ephialtes, Otus, and Antaeus–figures drawn from distinct traditions to frame the gate and the pit. Nimrod anchors the biblical line, linked to Genesis and the Babel project, beginning a chain of hubris that later languages would complicate as babel. Ephialtes and Otus belong to Greek myth as the Aloadae, whose elevated schemes test the heavens; Antaeus, also Greek in origin, remains a towering earth-born figure whose strength comes from touching the ground. these figures set the tonal contrast of power, pride, and fate around the walls and bank of the scene.

Nimrod began the Babel enterprise; Genesis ties him to the tower whose reach mocked the divine order, and the resulting gibberish of languages still echoes as a motif in this moment. His head and broad shoulders loom near the bank and walls, signaling a beginning that makes the reader weigh the idea of human ascent against cosmic limits.

Ephialtes and Otus move around the gate as twin giants with a single, conspicuous pride. Their idea to topple Olympus makes them proud beyond measure, and their presence emphasizes intellect turned to overreach. Whether they intend to bend fate or merely prove their power, their stance–hands raised, chins up–reads as a test of will against the sacred order, a scene that underscores the peril of overconfidence in Rome’s literary memory as well.

Antaeus stands apart: earth-born strength that grows when he touches soil. His strong hands grasp the travelers and, with a mighty lift, move them down toward Cocytus. The waist and broad frame anchor his role, while the bank of the icy lake around him marks the transition into the lower circle. This figure embodies the principle that true power derives from the ground, not from presumptuous ascent, and he embodies the move from spectacle to consequence.

Together these sources create a cross-cultural mosaic that links biblical memory with Greco-Roman myth. The number of giants signals a polyphonic approach to hubris and its penalties, a story that resonates with later Rome’s tradition and its writers–scipio among them–who framed walls and city ambition as moral tests. If youre looking for the underlying idea, it’s this: pride builds monuments, but the earth and the gods keep the score, so the scene remains a powerful reminder of every civilization’s limits and fears.

Placement within the Inferno: the canto’s position in the narrative arc

Recommendation: Position this section at the threshold between the opening introduction and the deeper descent, so it acts as a hinge that defines how the arc will proceed and what will be tested next.

-

Position in arc and turning point: This segment sits at the boundary where the living world yields to the underworld; the turning point of the opening arc is here. The gate does more than admit; it reveals a need to take a stance, and the neutrals who there stood, tall towers of ambition, echo the times and the Babel-like impulse to choose, though later the circles will test. Rome and other ancient references are invoked as frames for fame and strength, and the names of hercules, scipio, achilles, hannibal anchor the measure of strength across times, helping understand what comes next and what it requires from those who know.

-

Narrative function and Virgil’s guidance: The section solidifies the guide’s authority and frames the descent as a tested moral inquiry. Those who follow the mentor’s logic learn to expect that actions, not appearances, will be weighed. The advice given here takes on lasting weight, and the narrator’s trust in the guide signals how the ensuing circles will demand resolve and discernment.

-

Imagery and classical allusions: Across the boundary, rome’s memory and babel-like confusion converge, while tall towers of ambition loom as symbolic height. There is a cadence of names–briareus, hercules, scipio, achilles, hannibal–used to set a scale of strength. The sound of voices from those times and peoples travels down the corridor, inviting understanding and know of how such exempla will govern later judgments, and there stands a reminder that the same method will be tested again for those who come after.

-

Reading strategy and takeaways: Note the turning-point signals–the gate’s inscription, the insistence on a moral stance, and the move from outline to depth. When mapping the narrative arc, identify how this boundary frames the action that follows and how the examples (hercules, scipio, achilles, hannibal, briareus) are used to calibrate strength and choices. Wonder about how the same approach will apply to those who follow, and know that the structure relies on reaching a higher level of discernment as the journey proceeds.

Virgil’s guidance: how he leads and what he communicates to Dante

Follow virgil’s method: listen actively, test each scene, and let reason bound to empathy guide your steps through malebolge. He began by setting a firm frame so dante stays oriented, even when many horrors loom here and around.

virgil communicates a core ethic: every punishment mirrors the sin, a case that reveals inner logic. He draws on greek tradition to describe the correspondences, noting how hercules and achilles would recognize a failure of virtue. The approach seems daunting, yet much of the clarity stems from these references that dante could recall.

When antaeus appears, virgil uses the moment to illustrate how strength can be used for ascent when bound to purpose. The giant’s lift is an action that serves moral instruction; virgil points out that the ascent depends on disciplined observation rather than panic, and that the traveler should stand apart from the crowd so as to hear the moral note clearly.

virgil’s communication style stays precise and measured: he describes sights, names the fault, and asks questions that prompt action. Though the path is hazardous, he is with dante every step, standing apart from the chaotic many voices and providing a clear sign when encountered dangers arise. The exchange seems focused on what is most strong: a reliable method to interpret each symbol and case.

The practical result is a map dante can carry: an east–west sense of virtue and vice, a way to know what to trust and what to doubt. virgil’s counsel could be described as a tutorial in discernment, turning what is seen here into guidance for what to do next with the souls and the many peoples encountered around. The pilgrim stood with renewed focus, and the mentor’s calm voice became the most strong anchor as he moved here toward the lowest depths.

Dante’s response: narration style, emotion, and character development

Begin with a brief, plain close-reading of the voice: the narration moves to a shouted address above the scene, a deliberate contrast that sharpens emphasis and makes the cadence feel immediate.

Emotion tightens as the narrator toggles between restrained description and bursts of passion, with sounds that travel through the walls of malebolge and signal revolt without losing control–likely noted by readers.

The master frame leans on greek myth to fortify the voice: hercules and briareus loom as grand figures, antaeus chained, still and standing, with jupiter present as a distant authority above the eighth circle. This mythic scaffold clarifies pride and revolt among the giants, and the narrator grows from detached observer to engaged commentator who notes what is at stake for the peoples, the proud, and the damned.

To apply this lens, trace where the master voice tightens, noting moments when the speaker could only be attempting to balance awe with clarity.

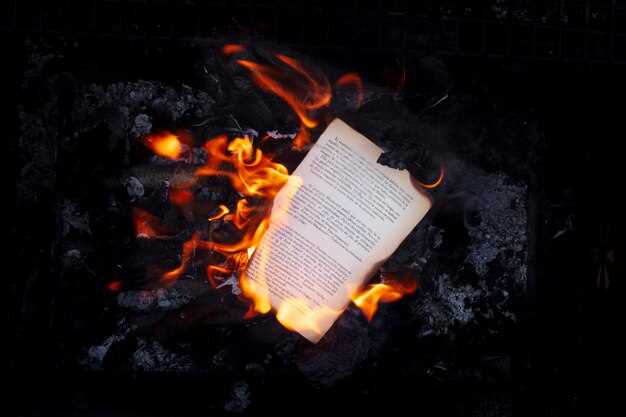

Symbolism and themes: giants, power, hubris, and divine order

Identify how the mighty giants symbolize hubris and how divine order enforces balance; map their positions to the bottom level and the walls over the city, and compare them with typhon in the idea that revolt would challenge what is owed to the order. In dantes commentary, the bank of tradition anchors strength while warning travelers that every overreach were met with accountability, and that the idea of restraint defines a kind of justice.

- Giants embody overreaching power and threaten travelers, each step forward testing the boundary between human aspiration and cosmic law; their presence makes the level feel heavier and the bottom even more pronounced.

- Hubris as the central flaw: mighty figures pursue dominance, yet the divine response reasserts order; strength here is measured by discipline rather than force, and later turns into a caution about what would happen if restraint fails.

- Divine order as architecture: walls encircle the scene, the city’s geometry implying a moral map where every level holds a rule, and the bottom acts as a stark reminder of consequence when boundaries are crossed.

- Mythic and historical echoes: Typhon aligns with ancient traditions, while zama and references from rome and the east show that authority and its limits travel across banks of culture; the idea of authority travels far, and the whole mechanism is designed to take control away from the reckless and place it back upon the rightful scale.

- Symbolic instruments: an arrow marks direction and penalty, a tool that signals the path of punishment against excess; the number of wounds or denials tallies the offense and clarifies how the revolt is checked.

Further, the interpretation foregrounds that every figure, from the mighty giants to the unseen reader, plays a part in the larger scheme: the bottom of the pit, the walls surrounding Hell, and the city’s invisible order all work together to maintain cosmic balance. when readers take this map, they can see how dantes also frames power as a test of restraint rather than a showcase of force; the idea is to prevent the misstep that would upset the entire system. In this sense, the journey becomes a commentary on how strength, if misused, would topple the orderly design, and how the east and west borrow motifs to reinforce a single, shared rule. The giants are not merely obstacles; they are necessary counterweights that keep the whole structure from wobbling, and they remind us that the balance would fail without a firm, divine-guided framework that even the mightiest cannot overturn.